LSP - The Liskov Substitution Principle

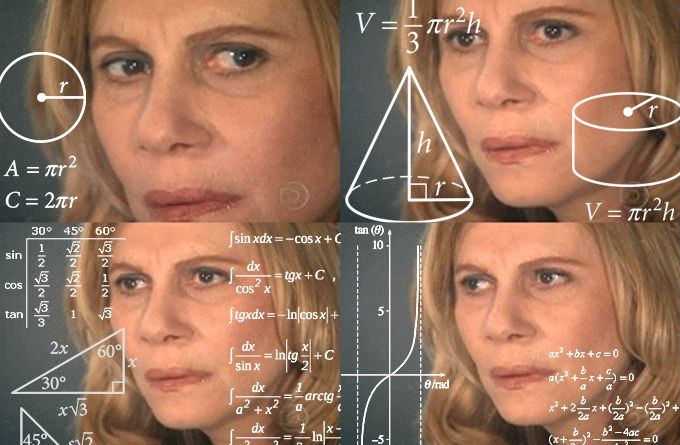

The LSP (Liskov Substitution Principle) is another of the 5 SOLID Principles that every good programmer and/or software architect should know. However, it requires special attention because it is abstract and more difficult to understand, especially for those starting with SOLID.

Definition of LSP

Barbara Liskov, in May 1988, wrote the following text to define subtypes:

If, for each object o1 of type S, there is an object o2 of type T, such that, for all programs of type P, it is not modified when o1 is replaced by o2, then S is a subtype of T.

Yes! The brain knot happens naturally when you first come into contact with this definition. But don't despair because the text written by Liskov can be simplified and understood as:

Whenever the program expects to receive an instance of a type T, a subtype S derived from T must be able to replace it without the program needing any adaptation to handle an instance of subtype S. Otherwise, S should not be a subtype derived from T.

Important: ⚠️

👉 LSP is not just about guidance on the use of inheritance. Over the years, LSP has become a software design principle applicable to any type of interface and implementation.

👉 More broadly, the secret to success is preserving expectations and ensuring that the behavior of subtypes is compatible with the intention of the base type.

With this summary, we can move forward.

Violation of LSP

I've put together an example in .NET C# (simple and for educational purposes) that should help understand one of the ways to violate the Liskov Substitution Principle.

Observe calmly each of the classes:

public class Vehicle

{

public bool IsIgnitionOn { get; protected set; }

public bool IsMoving { get; private set; }

public virtual void StartIgnition()

{

this.IsIgnitionOn = true;

}

public void StartMove()

{

this.IsMoving = true;

}

}

public class Car : Vehicle

{

public override void StartIgnition()

{

this.IsIgnitionOn = true;

}

}

public class Motorcycle : Vehicle

{

public override void StartIgnition()

{

this.IsIgnitionOn = true;

}

}

public class Bicycle : Vehicle

{

public override void StartIgnition()

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

Now let's see what happens when we execute the StartIgnition method for different instances of Vehicle:

public void StartVehicleIgnition(Vehicle vehicle)

{

vehicle.StartIgnition();

if (vehicle.IsIgnitionOn)

{

Console.WriteLine(

$"The vehicle has the ignition on.");

}

}

StartVehicleIgnition(new Vehicle());

// ✅ The vehicle has the ignition on.

StartVehicleIgnition(new Car());

// ✅ The vehicle has the ignition on.

StartVehicleIgnition(new Motorcycle());

// ✅ The vehicle has the ignition on.

StartVehicleIgnition(new Bicycle());

// ❌ NotImplementedException

In this case, it's evident that, although a bicycle is a vehicle, in the scope of this program, an instance of Bicycle cannot adapt to the StartIgnition method and even less to the IsIgnitionOn property that represents an internal state inherited from the base class Vehicle.

Modifying the program, including error handling to serve exclusively one or more instances of Bicycle, should be considered a crime.

But as I always say: You're not here by chance! The entropy of the universe, in a singular way, brought you here and now you'll have a good example to share with your colleagues so they also don't make this kind of error anymore.

Application of LSP

To fix and prevent problems like these from occurring, we could follow the following approach:

public class Vehicle

{

public bool IsMoving { get; private set; }

public void StartMove()

{

this.IsMoving = true;

}

}

public interface IVehicleMotorized

{

decimal IsIgnitionOn { get; }

void StartIgnition();

}

public class Car : Vehicle, IVehicleMotorized

{

public decimal IsIgnitionOn { get; private set; }

public void StartIgnition()

{

this.IsIgnitionOn = true;

}

}

public class Motorcycle : Vehicle, IVehicleMotorized

{

public decimal IsIgnitionOn { get; private set; }

public void StartIgnition()

{

this.IsIgnitionOn = true;

}

}

public class Bicycle : Vehicle

{

// Attributes and methods specific to bicycles.

}

In this case, we created an interface called IVehicleMotorized and made the Car and Motorcycle classes implement the properties and behaviors of our new abstraction.

As for the Vehicle class, we removed everything that cannot be used in bicycles and left only behaviors/methods that are directly related to what we call vehicles in the scope of this program.

Let's refactor the section where we use the StartIgnition method and the IsIgnitionOn property to ensure that only classes that implement the IVehicleMotorized interface can be triggered in the StartVehicleIgnition method:

public void StartVehicleIgnition(IVehicleMotorized vehicle)

{

vehicle.StartIgnition();

if (vehicle.IsIgnitionOn)

{

Console.WriteLine(

$"The vehicle has the ignition on.");

}

}

StartVehicleIgnition(new Car());

// ✅ The vehicle has the ignition on.

StartVehicleIgnition(new Motorcycle());

// ✅ The vehicle has the ignition on.

To conclude, let's create an example program where no unexpected behavior occurs when replacing the base class Vehicle with any of the other derived classes:

public void StartMoveVehicle(Vehicle vehicle)

{

vehicle.StartMove();

if (vehicle.IsMoving) {

Console.WriteLine("The vehicle is moving.");

}

}

StartMoveVehicle(new Vehicle());

// ✅ The vehicle is moving.

StartMoveVehicle(new Car());

// ✅ The vehicle is moving.

StartMoveVehicle(new Motorcycle());

// ✅ The vehicle is moving.

StartMoveVehicle(new Bicycle());

// ✅ The vehicle is moving.

We end here.

As mentioned, this was an example of one among other forms of violation of this principle. The discussion can be extensive and it's worth deepening according to the context of your system.

If you've already witnessed LSP violations, document the cases and their impacts to guide future decisions.

Thanks for reading. To deepen: Clean Architecture — A Craftsman's Guide to Software Structure and Design (Robert C. Martin, 2019).